No-nonsense journalism in the age of fake news

Christian Esguerra breaks down new trends, bias, and objectivity ahead of 2022 Elections

by Ralph Hernandez / December 17, 2021

In this so-called post-truth age, it’s a welcoming sign to see public trust towards news in the country increasing this year. In the latest Reuters Digital News Report, trust in Philippine news has improved to 32% in 2021 from 27% in the previous year. However, the National Union of Journalists in the Philippines (NUJP) pointed out in a statement that “we are far from out of the woods” as the figure is below the global rating of 44%, in itself described by the group as “alarming.”

As the 2022 Presidential Elections draws near, The Red Circle had the opportunity to talk with veteran journalist Christian Esguerra, host of ANC’s After the Fact, to discuss media ethics and standards, its evolving landscape, and the fight against disinformation.

Truth, objectivity and bias

You have probably seen it on different social media platforms: Users accusing media networks and news organizations of being “bias” when the proper term should be “biased,” the adjective form. Then again, being biased is not something that applies only to journalists and reporters.

“It’s something that you cannot avoid. Everyone has biases, journalists included. It’s how their perspectives were formed,” Esguerra explained. “For example, you have your religion, you believe in certain ideas and things that others do not necessarily share. That is your own bias, basically.” But becoming a journalist does not require erasing your biases, he added. “You can make sure that that bias won’t show in a news article, and at the same time, those biases or perspectives of yours won’t limit your view of the world.”

But how? And can journalists really be objective if they have personal biases? That’s where newsroom standards and editors come in, Esguerra said. “Sometimes, you would feel passionate about a particular candidate or against a particular candidate. Sometimes, the biases would show through the slant… maybe [you don’t] know any better, and that’s why you have editors: To tell you that this is not how you’re supposed to write news.”

Readers and audiences also have to learn, understand, and accept that the news being reported is the “truth in the meantime.” Journalism is an ongoing process, said Esguerra, and that the truth reporters have arrived at may not be the whole truth yet. “Basically truth that has been established based on the facts that we were able to gather and verify given the deadline. For instance, after a few months or after a few years, the truth that we were able to establish was not exactly the whole truth. You have to be open to changing that or refine it.”

Journalism trends and evolving landscape

Without going as far as content analysis, Esguerra shared that he has observed a “more conscious, earnest effort” from journalists and media organizations “to confront the problem of disinformation, not just misinformation” in the run-up to the national elections next year.

The problem has also ignited action, with publications like Philstar.com and Rappler, as well as groups like Fact Check Philippines and Commoner dedicating more time and effort to fact check viral social media posts. Facebook itself, back in 2018, partnered with VERA Files and Rappler for its third-party fact-checking program. Claire Deevy, then the Facebook Director for Community Affairs for Asia Pacific, said she hopes the partnership will “better identify and reduce the reach of false news that people share on our platforms.”

Fact checking is inherent to the job of the journalist, Esguerra said. It only warranted a separate section or category in news websites due to the proliferation of disinformation. “Technically, in the olden days, even before you write an article you’re already doing fact checking.” And now, while journalists are integrating fact checking in their reportage more often, Esguerra reminded them to avoid opinionating. Sometimes, he said “cold narration of facts” is better in delivering your point across.

There have also been calls to fight disinformation and misinformation on platforms like TikTok and YouTube, where they are arguably most rampant. According to the Reuters Digital News Report, Filipinos spend nearly 11 hours per day online, with more than four hours spent on social media. TikTok also became a destination for news among Filipinos at 6%, while Facebook remained at the top at 73%, YouTube at 53%, Facebook Messenger at 36% and Twitter at 19%.

Esguerra shares the sentiment that journalists and news organizations should also be breaking ground on different social media platforms to reach various audiences. However, he reminded them that they are there not to promote themselves or establish a larger following. “Even if journalists are getting a lot of exposure these days, you should also check your ego. Let your story, your body of work do the talking for you.”

Gearing up for the elections, against threats

Aside from fighting disinformation and fake news, journalists and news outfits making waves on social media platforms can also utilize their reach to strengthen its role as the watchdog of society. As the Commission on Elections expanded its rules on political ads run on social media, Esguerra stressed the importance of the role of the press and media before and during the election campaign so that voters can make an informed decision.

“Candidates can always go straight to the voters using their social media pages and websites. That’s automatically a one-sided approach meant to promote them. That’s why the media should always be in the middle, between the voters and the candidates.The media will tell the voters what’s true, what’s being exaggerated, and what’s being left out.”

The caveat, however, is that reporters and organizations almost always get backlash from the supporters of the candidate being fact-checked, he said. In fact, Esguerra himself has been on the receiving end of harassment and threats online and being accused of spreading fake news and being biased.

“I think the better response is to basically ignore them, which I have been doing for many years now. But there are some bashers who really cross the line.” And those should be taught a lesson, said Esguerra as he explained that “We cannot yield the conversation or the platform to fanatics making unfounded accusations or those issuing threats.”

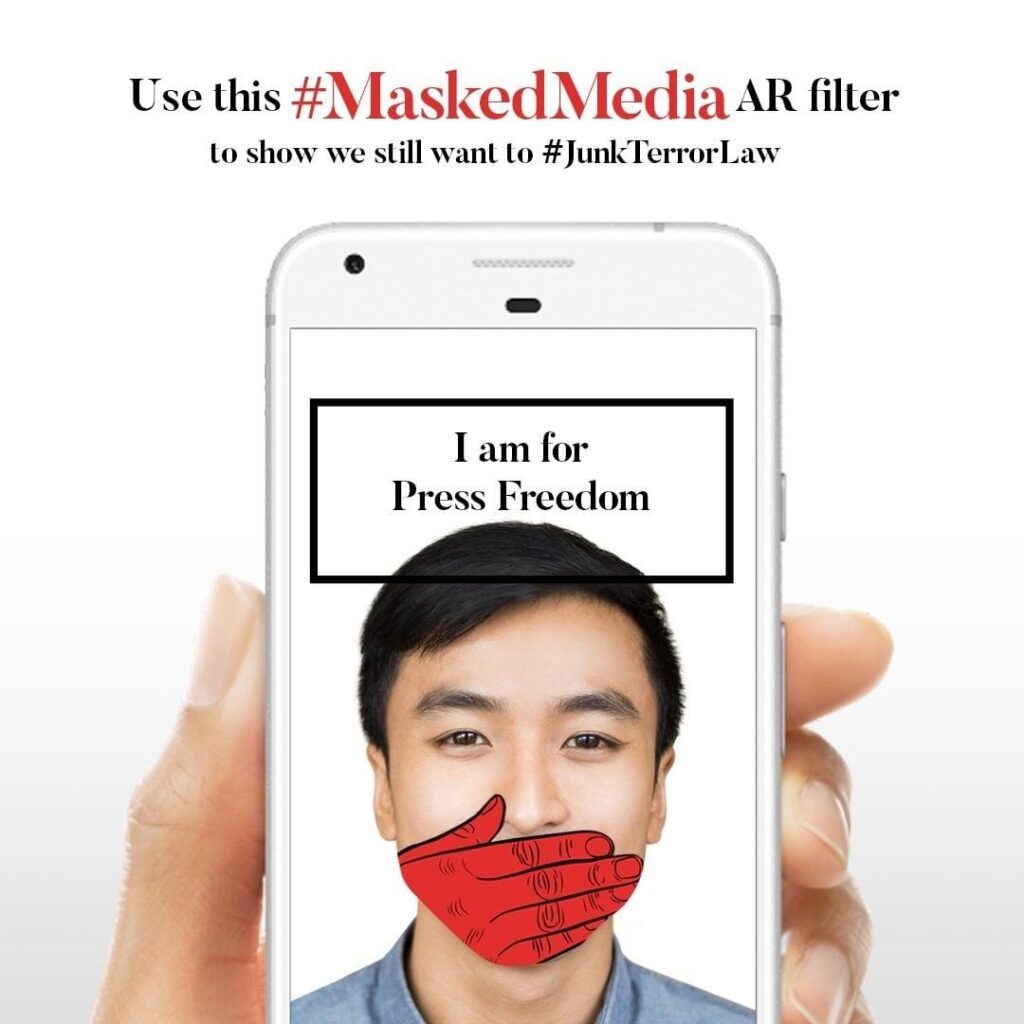

When threats can no longer be ignored as they affect one’s work, personal life and general well-being, Esguerra advised fellow journalists to report them to the National Bureau of Investigation or the NUJP. Recently, the union launched its #MaskedMedia movement where you can use an augmented reality filter to show support for press freedom and the campaign to junk the Anti-Terror Law. One can also support the movement by buying a face mask for P160. Its proceeds go to the legal defense fund for journalists.

“We all know that the free media are facing more pressure, greater challenges under the Duterte administration,” Esguerra recounted. The first Filipino Nobel Peace Prize laureate Maria Ressa, who’s also the CEO and co-founder of Rappler, said during her acceptance speech in Norway last December 10 that “What happens on social media doesn’t stay on social media. Online violence is real world violence.”

Ressa is only one of many journalists and media organizations known for their critical reportage on the Duterte administration who are facing charges and being red-tagged, a term for getting accused of being a communist or a supporter of the communist movement. In July 2020, ABS-CBN, the largest broadcast network in the country, was denied a franchise renewal by allies of President Rodrigo Duterte in the Congress. More recently, Energy Secretary Alfonso Cusi and business tycoon Dennis Uy, a major donor of Duterte’s campaign in 2016, filed libel suits against several journalists and news organizations for their coverage of the controversial Malampaya deal.

“Those instances of pressure coming from the President were also meant to send a message to the rest of the media that if you don’t toe the line, this is what would happen to you,” Esguerra told The Red Circle. He said the worst kind of censorship is self-censorship, which happens both consciously and unconsciously to some newsrooms and their reporters nowadays. “You don’t have to tell them to kill a story, they would do it on their own or sometimes, they would go for a softer angle.”

Aside from resisting the political pressure, Esguerra also warned journalists covering the presidential campaign trails against possible dilemmas that may hinder them from doing their job properly. “Sometimes their perspective becomes limited, they don’t see what’s happening outside the campaign trail involving the candidate that they’re assigned to cover. There’s also the problem of being too close to the candidate, the campaign team and strategists and sometimes your mind gets clouded and conflicted.”

The non-negotiables

Esguerra, who has been in journalism for over two decades now, started his career with the Philippine Daily Inquirer before joining ABS-CBN in 2015 first as a multimedia reporter, and now an anchor. He is also the host of a news podcast called Facts First, where he interviews public figures on relevant issues. Known by his students as Sir Ian, he has also been teaching journalism at the University of Santo Tomas since 2000.

He describes his view of the profession as “purist,” admitting that he has gotten several offers from the people he has interviewed but never accepted a single one. “Once you create that reputation, they will start refraining from offering again… These don’t just come from a particular group or person, almost all of them will test you. And not all will offer money, some will try to befriend you or invite you to places until you get a debt of gratitude.”

Esguerra also does not agree with the notion that the future of journalism is in the hands of “woke, privileged kids” posited by the Twitter persona Editors of Manila.

“Shortly before I graduated I was already looking for a job. I didn’t have the privilege to spend the next several months having no work.” He recounted his beginnings as a contributor, where he only got paid per published story. After a few months, he was eventually accepted, initially on probation status before getting regularized in half a year. “There are ways, if you really want your job and you really want to be a journalist… If you really think you’re better off being a journalist, you will find a way to stay in the industry and find no excuses to leave.”

So what does it take to be a good journalist, especially in this day and age? Esguerra said there’s no clear cut way to achieve this but a good start would be to develop your ‘BS detector.’ “You also have to have guts and you have to come prepared. You should know the issues and what you’re asking about. And if you’re asking softball questions, why even do journalism?”

Read also

- Speak up, act and empower

- “A little different, but the fun remains”

- The Red Circle celebrates a year of meaningful storytelling